Sep 9 – Written By Michael Sparks

Crowding: Part One

Are the National Parks Too Crowded? It’s Complicated.

Some parks are crowded in some places.

After a road trip to several national parks, a visitor had this to say: “Visitor concentration points can't be kept in sanitary condition. Comfort stations can't be kept clean and serviced. Water, sewer and electrical systems are taxed to the utmost. Protective services to safeguard the public and preserve park values are far short of requirements. Physical facilities are deteriorating or are inadequate to meet public needs.” With all the recent clamor about overcrowding in the national parks, you’d be forgiven for thinking this was last week. But, no, Charles Sevenson wrote that report in Reader’s Digest in 1955.

Since then, overcrowding hasn’t gone away, and has only taken on an increased urgency over the last several years. 2019 was the busiest year ever for America’s 63 national parks. With much of the country emerging from Covid lockdown this summer, 2021 is on pace to be even busier. The Senate’s Subcommittee on National Parks even held a recent hearing to address the issue.

National parks are meant to be a refuge, a place to experience the beauty of nature and draw strength from solitude. It can be hard to do that if you have to wait two hours for a parking spot, just to then get elbowed by a tour group at the lookout point. Not to mention the threat of ecological damage, which goes up as visitation increases.

The fundamental cause of overcrowding, as Kevin Gartland, Executive Director of the Whitefish, Montana Chamber of Commerce noted in the Senate subcommittee hearing, is that “supply and demand doesn’t apply here. The demand is there…but we can’t just go out and build more” national parks.

What much of the current conversation lacks, however, is a more nuanced understanding of the issue. Much of the talk revolves around hyper-popular parks like Zion, Glacier, Acadia, and the Grand Canyon. Busy parks, to be sure. But it is not the case that all parks are crowded all the time. Some of our national parks are crowded, in some places, some of the time.

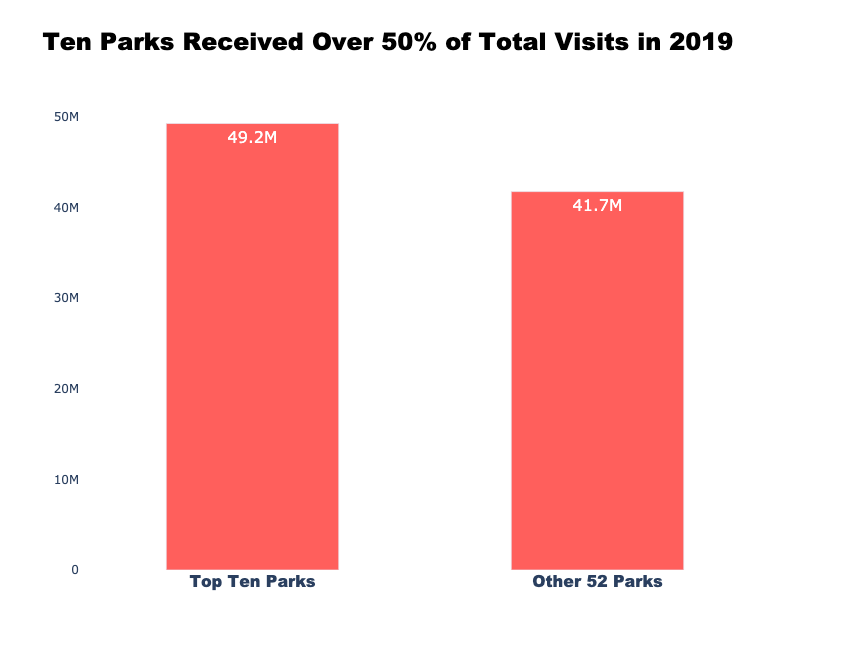

“Crowding is certainly an issue, but it’s usually localized,” Dr. Ryan Sharp, Associate Professor in Park Management and Conversation and Co-Director of the Applied Park Science Lab at Kansas State University told me. “A lot of the crowding we read about now is concentrated in the bigger parks. There’s lots of parks out there not seeing those crowded conditions, but everyone wants to go to Yosemite and Yellowstone and Glacier, so those places get super congested.” In fact, in 2019, 10 of the then 62 national parks received over 50% of all total visitors.

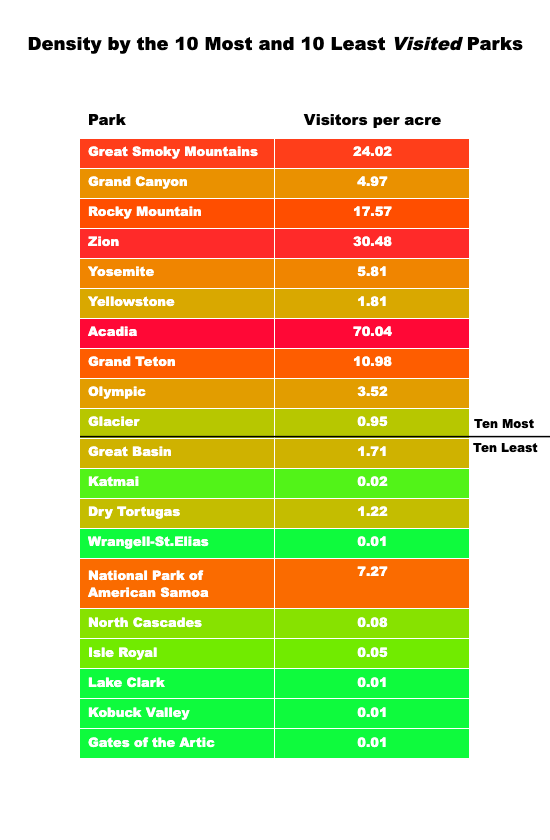

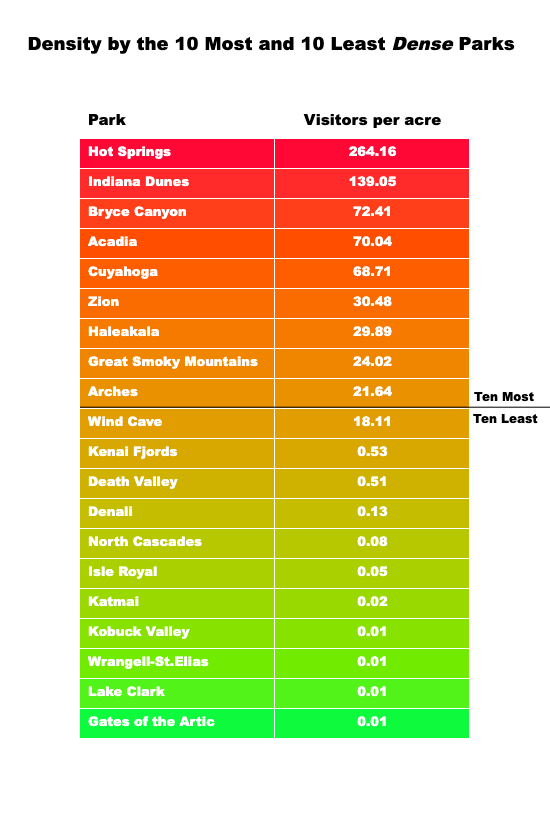

Moreover, the National Park Services collects relatively few details on visitation and mostly relies on top-line numbers. Total visitation, though useful, does not tell the complete story. “Yellowstone is 2 million acres, but the vast majority of that is wide open if people are willing or able to wander away from their vehicles,” Dr. Sharp said. Looking at density, in terms of visitors-per-acre, gives another view of how crowded parks are. The most popular parks are not always the most dense.

And the densest parks are not always the ones we think of as the most crowded.

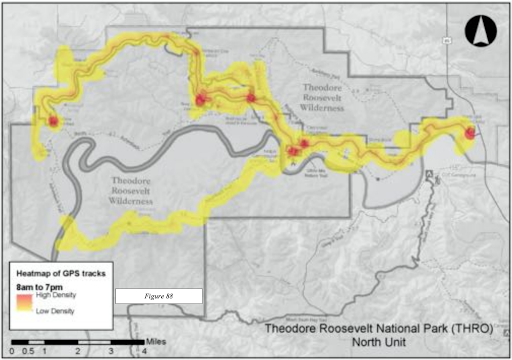

Often, a park’s infrastructure (roads, trails, lookout points) funnels visitors to common points, and most visitors won’t (or can’t) make the effort to get off the beaten path. Unfortunately, the NPS collects very little publicly-available data on how visitors recreate within the parks. But, according to a 2019 study Dr. Sharp and his colleagues conducted at Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota, while about 70% of visitors to the park’s north unit venture away from the road, they hike only one mile on average. Moreover, they only spend about two and a half hours in the park, the vast majority of that time driving. In other words, visitors are not exactly experiencing the full nature of the park.

To determine this, Sharp and his colleagues handed out GPS trackers to visitors, who would then slip them in their pockets and forget about them as they went about their days. They then used the location data to build heat maps showing that visitors stuck mainly to roads and lookout points (and parking lots) and rarely ventured off-trail, even though Theodore Roosevelt is a “free hike” park, where visitors are encouraged to strike out on their own paths.

This is, of course, one study in one park and needs to be replicated many times over, but anyone who has ever visited a national park knows this to be pretty accurate.

When I visited Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota earlier this summer, the only time it felt even remotely crowded was while waiting in line for a cave tour ticket. While hiking the 44-square miles of mixed-grass prairie and ponderosa pine forest that makes up the rest of the park, I saw more buffalo than people (literally).

“We are not crowded on the surface,” Tom Farrell, Wind Cave’s Chief of Interpretation told me later via email. “If you want to get away from the people, get away from the asphalt.”

Since roads are such a main locus for visitors, you would think the NPS would have detailed data on vehicular traffic. But, again, no. When I reached out to the NPS for data on the number of cars in the parks, their spokesperson told me that data was unavailable because it isn’t tracked consistently across parks.

If the discussion around crowded parks is going to lead to improved visitor conditions and conservation efforts, then it must be a more informed and more nuanced discussion than is currently happening.